Bianca’s Writing Journey

2013

2013

When I became a full-time writer in May 2013, I don’t mean to say that I gave up my day job and depended happily ever after on my writing. No, what I mean to say is that I had no day job—and not for a lack of trying. I had two things working against me; I was a mother and an immigrant. But that’s another story. With nothing to lose and no more excuses to delay my long-suffering writing dream, there was no better time to start. So, I created a blog, and off I went.

Apart from the 3 poems published in two different print anthologies in 1999 and 2001, I had no idea if my poetry would resonate with an audience. Fortunately, the poems did resonate and within a 6 month period I had grown a healthy following and gained a clear idea for my first poetry book—Death and Life.

Once I familiarised myself with available publishing options, it became evident that University Presses, who published academic poets, dominated the poetry market, and traditional publishers did not accept poetry submissions because they considered it a niche market. This explained the trend of poets submitting single poems to online journals—an option that didn’t appeal as an ongoing endeavour, because I viewed it as a fruitless exercise in seeking external validation and constructing poems to fit someone else’s mould. Still, the stigma of self-publishing bothered me, so, before I made any decisions, I researched the history of publishing. My research resulted in an essay called The Publishing Class System, which only served to reinforce my anti-establishment sentiment and paint the indie route as an entrepreneurial path that better served my personal philosophy and writing future.

Some would say that I chose the easy option, but don’t believe that for a second. When I published Death and Life, I had no idea how technically challenging the process would be, and to say the results were disappointing is a huge understatement. The entire process involved one compromise after the next—everything from the cover to typesetting to typography. When I received the first proof copy I wanted to cry, because the book did not look, feel, or communicate my original vision. It was also expensive, because I had to pay for multiple proof copies to be shipped from the US to Australia, and I was never satisfied with the quality of Amazon’s Createspace service. Angry with myself for failing, I pulled it from sale, did my homework, and started the process over again. I also gained a great deal more respect for publishing houses and the amount of work that goes into getting a book to market.

2014 – 2016

The second attempt was a vast improvement, but when Amazon failed to pay me my royalties (and continue to not pay me as long as copies of the book circulate), I knew that I needed to find a more professional option. On a sidenote, something wonderful did come out of that publication—a New York filmmaker approached me with a proposal to use my poem, Tree of Life, in a trailer for a short film.

In late 2014, I partnered with a graphic designer and co-founded Paperfields Press, with the intent to publish the kind of poetry that I liked to read. I was also convinced that there was a bigger market for poetry than traditional publishers thought. The majority laughed at me and said nonsense.

At that stage, IngramSpark was a professional option for independent presses (not the self-publishing option it is branded as today) so it required a financial and legal commitment on my part. Using money from my family’s single income, I registered Paperfields Press as a company, set up a professional account with IngramSpark, and purchased ISBNs.

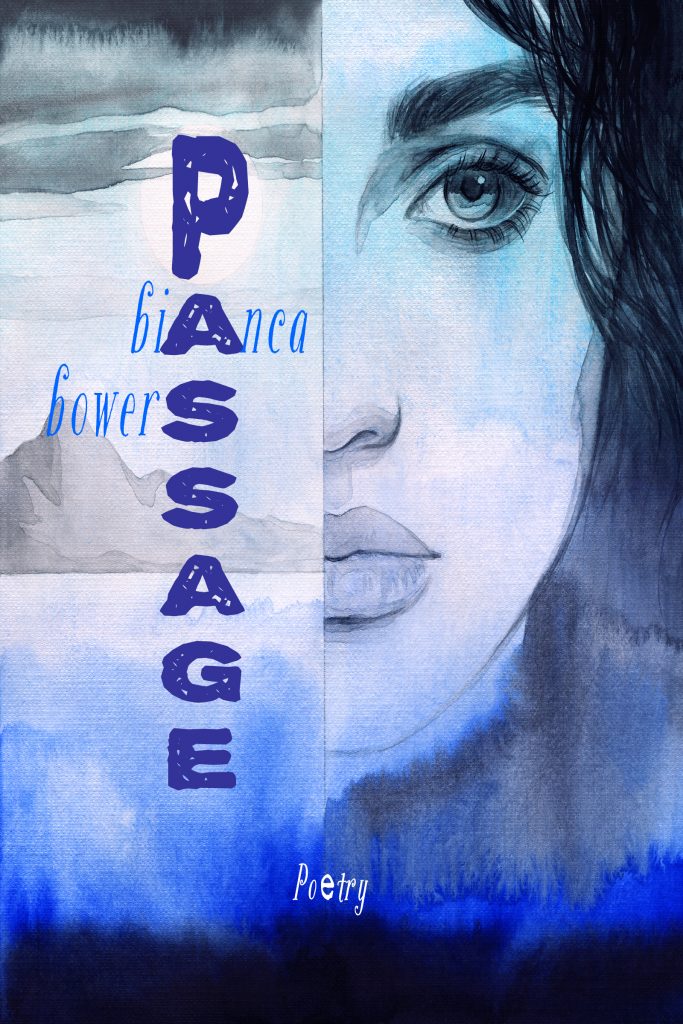

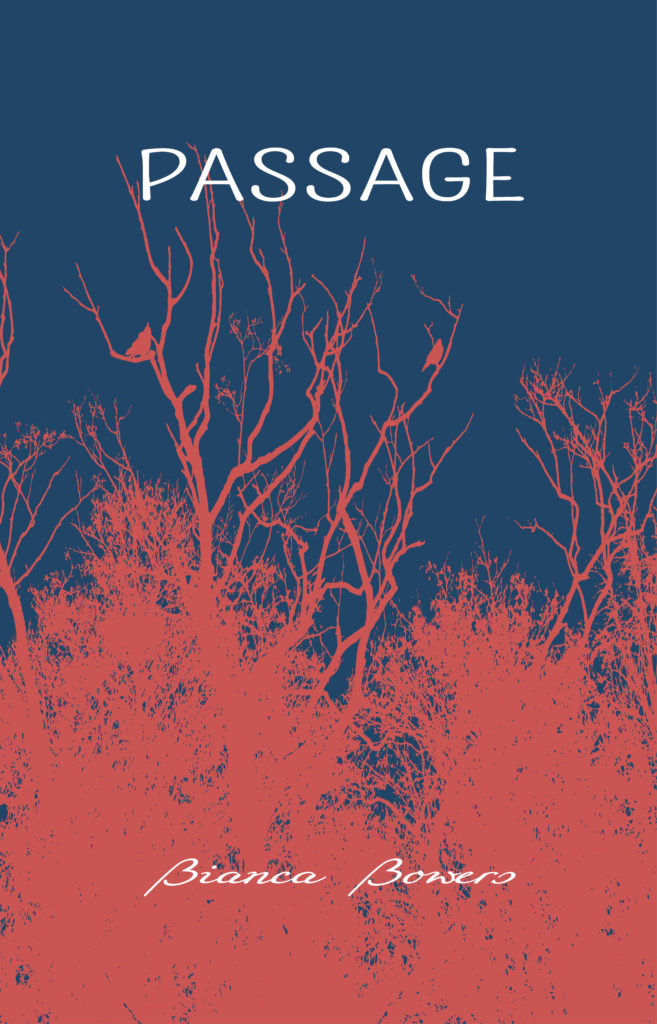

Three months in, my partner dropped out, but I had signed a Canadian poet and made financial and legal commitments, so I was determined to see it through. Using my book, PASSAGE, as the publishing guinea pig, I discovered LinkedIn Learning and learnt how to use Adobe InDesign to professionally typeset the book interior and design book covers. In addition to my book, I published the Canadian poet and later signed an LA poet. During this time, I attempted to reach out to similar small Australian presses and join networks, to give my authors the best exposure, but I was met with an elitist, non-inclusive, attitude. It did not endear me, and reminded me why I had chosen the indie route in the first place. It also led me to reassess my goals. I knew that to continue that path would mean sacrificing my own writing—something I had already done for the best part of 15 years. In early 2016, I closed submissions indefinitely, kept Paperfields Press as an imprint for my own poetry books, and focused on completing my first novel. Coincidentally, the instapoet movement exploded around this same time, which validated my belief that poetry was not as niche a market as traditional publishers had believed.

2016 – 2018

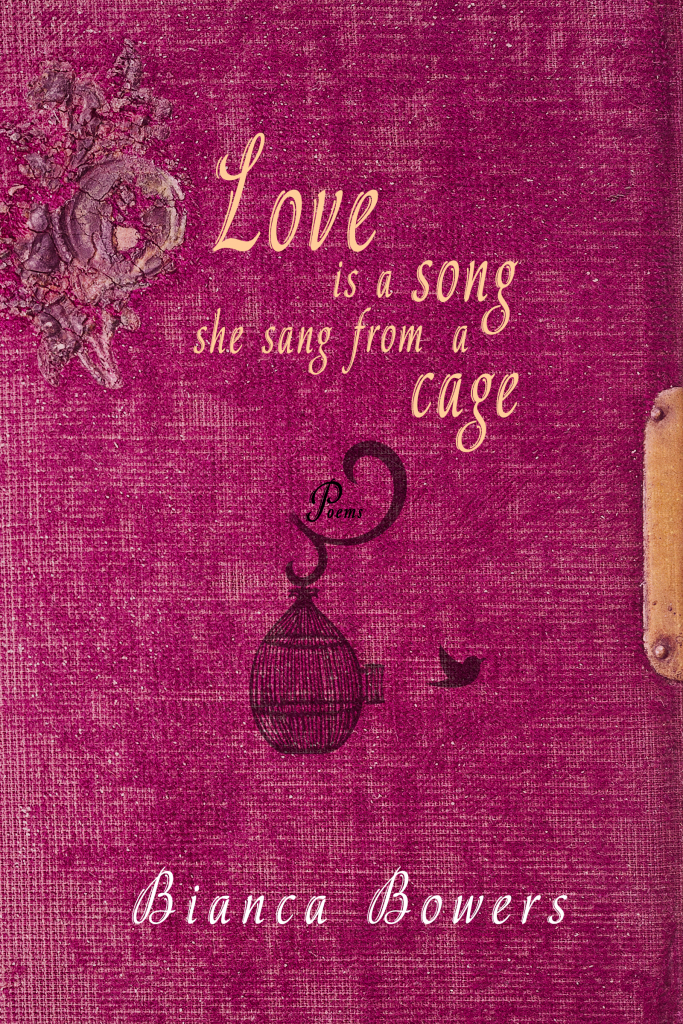

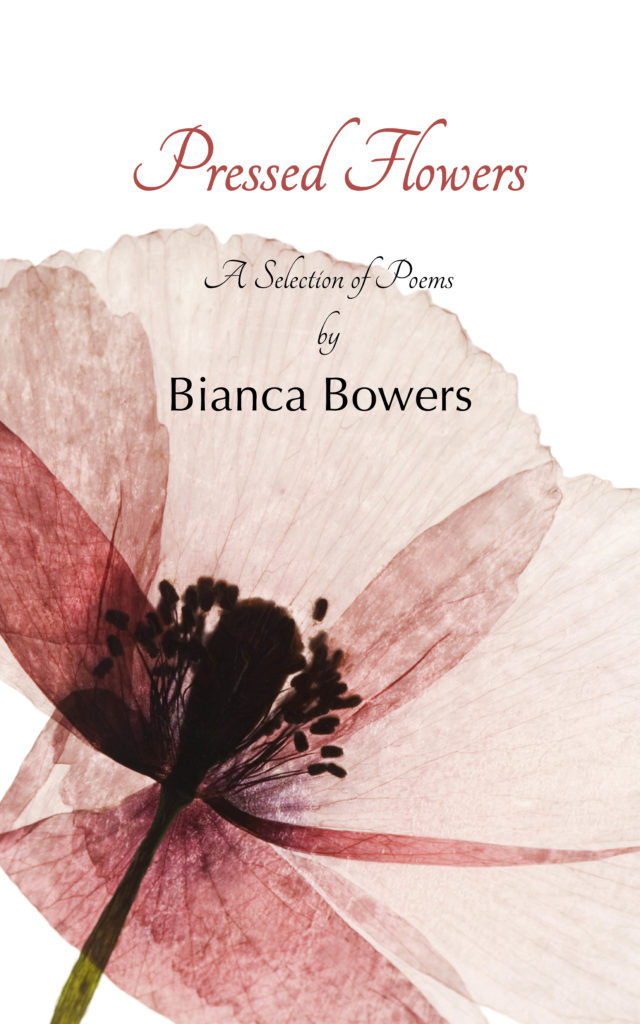

Over the next 2 years, I published my third, fourth and fifth poetry books – Love is a song she sang from a cage; Pressed Flowers; and Butterfly Voyage. I also completed my first novel and started writing my second. Wanting to step up my game, I also applied for, and got accepted to, a Master’s Degree in creative writing. Two papers later, I realised how much I did actually know, and how much I had learnt since beginning my writing journey in 2013. The brief stint at University also confirmed what I had known all along — the traditional publishing model is more akin to winning the lottery than it is a viable route to publication. Knowing that I didn’t have the funds to continue studying, even if I wanted to, I withdrew from the program and got serious about my writing future. Other than ego and external appearances, what did I hope to gain from a traditional publisher? Did I want to spend an unknown amount of years, as well as valuable writing time, submitting blindly and begging for validation crumbs? Realistically, unless your book becomes a mega success and you gain access to the 1% of Writers (like Rowling and King), you will never make a living under the antiquated traditional publishing royalty system. Similarly, if I finally got accepted by some obscure independent press, did I want to hand over creative control of my work? Having spent 5 years learning about publishing the hard way and moving ever closer to perfecting the process, wasn’t it ludicrous to stop?

Over the next 2 years, I published my third, fourth and fifth poetry books – Love is a song she sang from a cage; Pressed Flowers; and Butterfly Voyage. I also completed my first novel and started writing my second. Wanting to step up my game, I also applied for, and got accepted to, a Master’s Degree in creative writing. Two papers later, I realised how much I did actually know, and how much I had learnt since beginning my writing journey in 2013. The brief stint at University also confirmed what I had known all along — the traditional publishing model is more akin to winning the lottery than it is a viable route to publication. Knowing that I didn’t have the funds to continue studying, even if I wanted to, I withdrew from the program and got serious about my writing future. Other than ego and external appearances, what did I hope to gain from a traditional publisher? Did I want to spend an unknown amount of years, as well as valuable writing time, submitting blindly and begging for validation crumbs? Realistically, unless your book becomes a mega success and you gain access to the 1% of Writers (like Rowling and King), you will never make a living under the antiquated traditional publishing royalty system. Similarly, if I finally got accepted by some obscure independent press, did I want to hand over creative control of my work? Having spent 5 years learning about publishing the hard way and moving ever closer to perfecting the process, wasn’t it ludicrous to stop?

2019

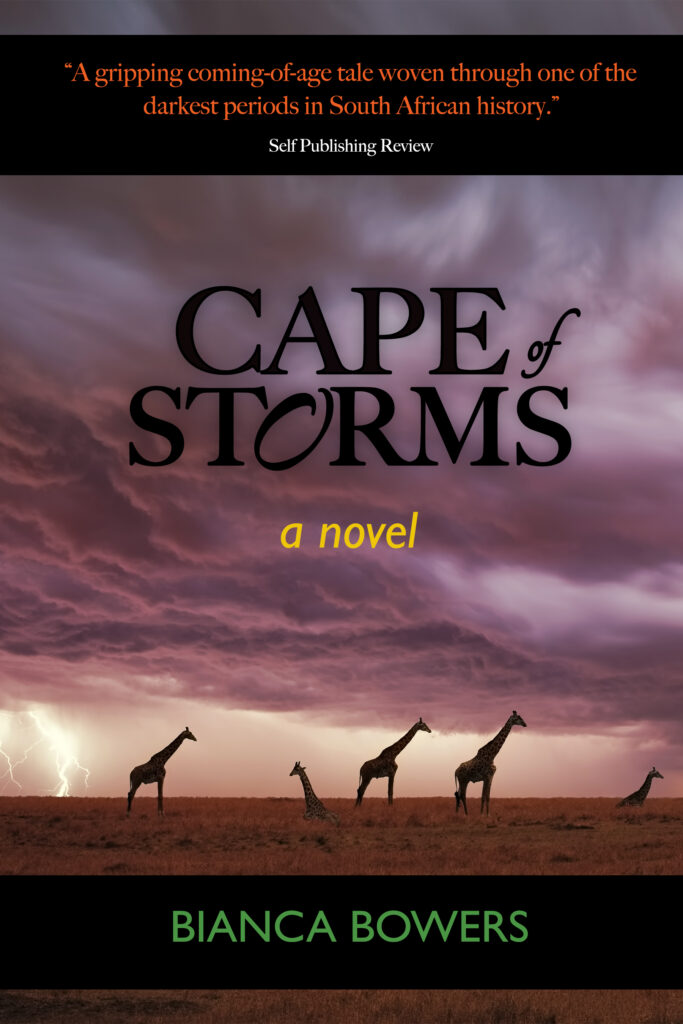

The year I published my first novel, I entered another round of soul searching and scrutinising the traditional publishing industry. Around the same time, stories were surfacing about publishing houses using sensitivity readers to modify or remove what they deemed to be politically incorrect content and words. Given that my novel, Cape of Storms, is a no-holds-barred coming-of-age story set in South Africa during and post-apartheid, I knew that the content would be enough to make any publisher squirm. And, if it was picked up by a publisher, they would want to carve out too much of the raw, ugly truth that the book is intended to convey. Considering my strong creative vision, and given I had spent 20 years working on Cape of Storms, I finally acknowledged and accepted that I had earned the right to be my own authority on what I wrote and published, and the concept of Auteur Books began to form.

The year I published my first novel, I entered another round of soul searching and scrutinising the traditional publishing industry. Around the same time, stories were surfacing about publishing houses using sensitivity readers to modify or remove what they deemed to be politically incorrect content and words. Given that my novel, Cape of Storms, is a no-holds-barred coming-of-age story set in South Africa during and post-apartheid, I knew that the content would be enough to make any publisher squirm. And, if it was picked up by a publisher, they would want to carve out too much of the raw, ugly truth that the book is intended to convey. Considering my strong creative vision, and given I had spent 20 years working on Cape of Storms, I finally acknowledged and accepted that I had earned the right to be my own authority on what I wrote and published, and the concept of Auteur Books began to form.

“Some of us have great runways already built for us. If you have one, take off. But if you don’t have one, realize it is your responsibility to grab a shovel and build one for yourself and for those who will follow after you.” ~ Amelia Earhart

2020

Unlike the rest of the globe, I did very little writing during Covid. Partly because my freelance editing business took off, but mostly because I reached the crossroads in any creative’s journey where I had to ask the question: Do I continue at great financial and personal cost, or, do I quit?

Unlike the rest of the globe, I did very little writing during Covid. Partly because my freelance editing business took off, but mostly because I reached the crossroads in any creative’s journey where I had to ask the question: Do I continue at great financial and personal cost, or, do I quit?

In a sense, I was no better off than my traditionally published counterparts in that I could not rely on my book sales to sustain me financially. And, while I knew that quitting wasn’t an option, I also knew that I could not continue in the same vein. Something had to give. I was nearing half a century on this planet and I still didn’t own my own home due to the lack of employment opportunities after having children. After 8 years of independent publishing and “following my bliss”, I had to admit that I was far from blissful; I was dying—not in a physical sense, but on an emotional, spiritual, and psychological level. My self-esteem had dropped dangerously low and I had to pull it out of the abyss; I had to try and rescue and salvage myself before it was too late.

2021 – 2025

I had to dumb myself right down to get that first employment contract—my resume was half a page, stripped of education and experience—but getting my foot in the door was all I cared about. I proved myself quickly and had an opportunity to progress, but I wanted more and I had finally reached a point where I could see my value again. I also wanted a career, not a job, so I set my sights on the next step and grabbed it when the opportunity arose.

I had to dumb myself right down to get that first employment contract—my resume was half a page, stripped of education and experience—but getting my foot in the door was all I cared about. I proved myself quickly and had an opportunity to progress, but I wanted more and I had finally reached a point where I could see my value again. I also wanted a career, not a job, so I set my sights on the next step and grabbed it when the opportunity arose.

Three roles later, I have laid the groundwork for my new career, we have built a home, and I’m still writing. I published my sixth poetry book in 2023 and my second novel in 2024.

As I write this in January 2025, I am entering my 12th year of independent publishing. Looking back, my writing journey has certainly seen ups and downs, highs and lows, but on the whole I have learnt so so much and I have done it on my own terms. I do not outsource any part of my creative project—I write and edit, I typeset my books, I design my book covers, I write the book blurbs and descriptions, the metadata and marketing material. I even manage my own websites.

In short, I am proud of what I have accomplished on my own and with limited resources. But the thing I am most proud of is the way I have retained my creative authenticity and stuck to my creative vision for my creative work. I don’t write to trends or follow formulas, and, like my imprint, Auteur Books, I am the author of my work in every sense. On that note, I will leave you with one of my favourite quotes of all time—a quote that sums ups my guiding principle for the work I publish:

“So much of what I see now feels recycled, redundant… built for an audience that already exists as opposed to in search of a new one. I’d want to promote artists that are digging deeper, that are looking for something amorphous that haunts them, that haunts me, that I just don’t have the language for.”

~ Source: https://tvshowtranscripts.ourboard.org/viewtopic.php?f=56&t=34927

If you’ve made it this far, you might also be interested in the following links:

- ARTISTS CV

- The deliberate typo in PASSAGE unveiled. Is it worth taking a creative risk in web 2.0 era?

- The Passage of a little salmon (2015 Archive)

- The Journey to 100k